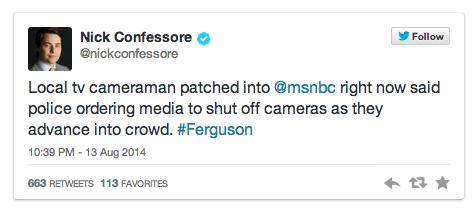

A suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, has been under a dramatic siege since Saturday, when a police officer shot and killed an unarmed black teenager named Michael Brown.

In the wake of the killing, protests have engulfed the community —

drawing a heavy-handed police crackdown with St. Louis County police

officers armed with assault weapons and outfitted with military equipment. Many of the striking images have come from reporters on the front lines, but also from citizens and their smartphones.

Around

10 p.m. Eastern on Wednesday night, a St. Louis County police line

demanded that a crowd of protesters turn off their cameras. Minutes

earlier, the police had ordered what appeared to be a peaceful crowd to

disperse, firing smoke grenades and rubber bullets. But none of them

have to turn their cameras off.

Here’s the deal: As a U.S.

citizen, you have the right to record the police in the course of their

public duties. The police don’t have a right to stop you as long as

you’re not interfering with their work. They also don’t have a right to

confiscate your phone or camera, or delete its contents, just because

you were recording them.

Despite some state laws that make

it illegal to record others without their consent, federal courts have

held consistently that citizens have a First Amendment right to record

the police as they perform their official duties in public. The Supreme

Court also recently affirmed that the Fourth Amendment, protecting

citizens from arbitrary searches and seizures, means that police need to “get a warrant” if they want to take your cellphone. (The ACLU has a concise guide to your rights, here.)

And the U.S. Department of Justice under President Obama has affirmed

the court’s stances by reminding police departments that they’re not allowed to harass citizens for recording them.

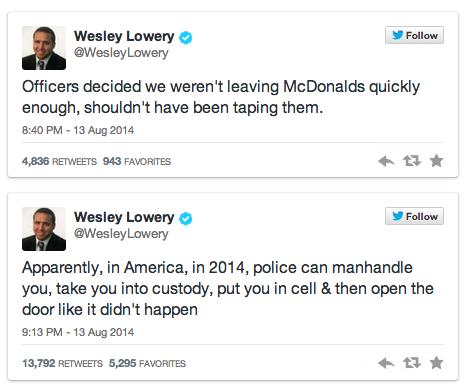

Sadly, these rights are not

always respected by the police. Even journalists are being harassed in

Ferguson in the course of their reporting. Earlier in the evening,

Washington Post reporter Wesley Lowery and Huffington Post reporter Ryan

Reilly were arrested in a McDonald’s and later released with no

explanation. Washington Post executive editor Martin D. Baron said Lowery was “illegally instructed to stop taking video of officers” and “slammed against a soda machine and then handcuffed.”

It’s obviously bad when reporters

are being arrested for no reason, but it’s important to remember that

all citizens — anybody who’s old enough to operate a smartphone — has a

right to record the official activities of police in public.