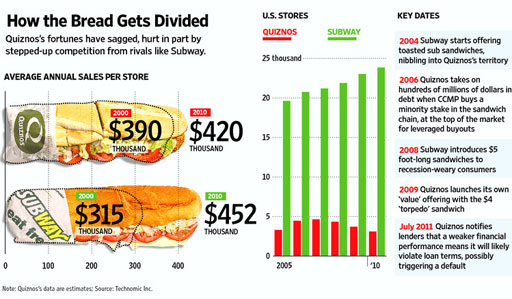

Sub Chain Loses 30% of Its Outlets; the $4 'Torpedo' Bested by the $5 Foot-long

Sandwich chain Quiznos made its name selling hot subs at premium prices, but a leveraged buyout at the top of the market and the recession helped turn that strategy to toast.

Now the company finds itself on the brink of default, also thanks to sour relations with franchise owners, costly rents and stepped-up competition from rivals like Subway. The chain now has about 3,500 stores, down from nearly 5,000 before the recession.

With sales sliding, Denver-based Quiznos told lenders July 8 that it would soon violate loan terms, which would put the chain in default and could trigger demands for immediate repayment of its debt.

The chain has hired Wall Street restructuring advisers to negotiate with its lenders, and said it has taken steps, such as cutting food costs, which it hopes will improve cash flow. But it continues to face business setbacks.

While executives are still analyzing second-quarter results, they told lenders the company's financial performance would be "materially below" previous projections, said people familiar with the matter. Quiznos, which doesn't publicly disclose its revenue, also told lenders that sales at stores open for at least a year were down 13% in May.

Quiznos's debt load stems in large part from a leveraged buyout five years ago. Quiznos took on hundreds of millions of dollars in debt in the deal, in which private-equity firm CCMP Capital Advisors LLC acquired a minority stake in the company. The chain is now owned jointly by CCMP and Consumer Capital Partners, an investment firm owned by Rick Schaden, who with his father bought the Quiznos franchise in 1991, when it had just 18 restaurants.

"Having a great deal of debt hampers your ability to grow because you're paying back interest, rather than investing in the brand," said Darren Tristano, executive vice president at restaurant consulting firm Technomic Inc.

"Before the recession, most of us believed the restaurant industry could continue to grow by leaps and bounds, so when you combine the recession with having a lot of debt, it creates two enormous barriers to success," he said.

Quiznos, formally QIP Holder LLC, was on a growth tear for much of the past decade, rapidly attracting franchisees as its hot sandwiches carved out a niche in the fast-food market.

The company required franchise owners, who paid it royalties on their sales, to buy their supplies from a Quiznos subsidiary, which became a sore point early on.

Franchisees have complained for years that the Quiznos unit charges substantially more than independent distributors for ingredients and other supplies.

Those claims were the basis for five class-action lawsuits they brought against the company in the 2000s. The chain denied that it was gouging franchisees and settled the suits in 2009 without admitting any liability.

"Our contention was that the way they structured the business didn't work. It wasn't just food—any item we used we were required to buy from Quiznos," said Chris Bray, former president of a Quiznos franchisee association that was a plaintiff in one of the lawsuits.

Some franchisees' struggles to turn a profit forced them to close, reducing Quiznos's royalty income.

Mr. Bray, who owned two Quiznos restaurants in Killeen, Texas, says he was sued by the company for bad-mouthing it to fellow franchisees and sold his two stores back to Quiznos in 2007, as part of his settlement. The company declined to comment.

By then, other fast-food operators, from Potbelly Sandwich Works to archrival Subway, had begun offering toasted subs, robbing Quiznos of its uniqueness. The recession only intensified the competition, and it didn't help that Quiznos outlets, with their premium-priced fare, tended to be in higher-rent areas.

When the economy sputtered, Subway, which dwarfs Quiznos with nearly 35,000 outlets world-wide, was quick to come up with a "value" offering—the $5 foot-long sandwich, which became a huge success. Quiznos responded with slimmer $4 "torpedo" sandwiches.

"It didn't take customers long to figure out that there was more value in the foot-long," said Dennis Lombardi, executive vice president of food-service strategies at restaurant development firm WD Partners.

More recently, Quiznos began offering $5 foot-long sandwiches. It also has tried to lure customers by promising everyday low prices, a strategy many franchisees fear will tighten the squeeze on their profits.

"This used to be a high-end product," said one Quiznos franchisee in Florida. Once Subway's $5 sub hit the market, Quiznos had to chase its competition, he said. Profitability waned "and stores started closing left and right."

This franchisee said he has been able to stay afloat only because he sets his own prices and hours and buys supplies from Sam's Club, in violation of company policy.

Quiznos Chief Executive Greg MacDonald said the profitability of franchise owners is the company's top focus. "Quiznos management has initiated cash-flow-improvement programs, such as lower food costs, reduced discounts and labor optimization," Mr. MacDonald said in a statement last week. "These recent cash-flow improvement programs have been a significant contributor to improving the financial health of our franchise owners."

Jason Medders, a Quiznos owner in Milledgeville, Ga., said he has faced the same challenges as other franchisees but that his store is profitable because "I go out there and work it every day."

Offering deals and discounts doesn't always work, however. In 2009, the chain tried a million-sandwich giveaway, but many operators didn't honor the coupons because they feared losing too much money, angering customers who came in seeking the free sandwiches.

"We're not McDonald's," Mr. Medders said. "You can't just open the doors and go to the golf course."

"You have to go out and give people coupons and let them know you're there. We haven't advertised on TV in quite some time, and people tend to forget you if they don't see you every day," he said.