A slim, 32-year-old psychologist, he spends his days behind a one-way mirror at Microsoft's (NasdaqGS: MSFT - News) video games research center here, watching people play the company's Xbox systems. He looks for smiles, listens for ecstatic squawks and logs triumphant gyrations. When a game is good, it elicits all the above and gets a "fun score" high enough for Microsoft to consider selling it.

And, of late, the fun quotient has skyrocketed.

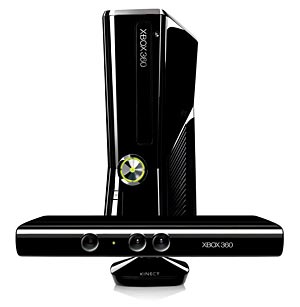

The company's blend of game developers, interface whizzes and artificial-intelligence experts has built Kinect, a $150 add-on for the popular Xbox 360 console that hits stores next month. With its squat, rectangular shape and three unevenly spaced eyes, this black device looks like a genetically underserved creature from "Star Wars."

Xbox Kinect |

In fact, Kinect arrives with a healthy dose of sci-fi trappings. Microsoft has one-upped Sony (NYSE: SNE - News) and Nintendo by eliminating game controllers and their often nightmarish bounty of buttons. Kinect peers out into a room, locks onto people and follows their motions. Players activate it with a wave of a hand, navigate menus with an arm swoosh and then run, jump, swing, duck, lunge, lean and dance to direct their on-screen avatars in each game.

"I can't tell you how many times I have seen people try and do the moonwalk," says Mr. Nichols, as he recalls their first, curious encounters with their virtual mimics.

Kinect also understands voice commands. People can bark orders to change games, mute the volume or fire up offerings, like on-demand movies and real-time chatting during TV shows that flow through the Xbox Live entertainment service.

The mass-market introduction of Kinect — with its almost magical gesture and voice-recognition technology — stands as Microsoft's most ambitious, risky and innovative move in years. Company executives hope that Kinect will carry the Xbox beyond gamers to entire families. But on a grander note, the technology could erase a string of Microsoft's embarrassing failures with mobile phones, music players, tablets and even Windows from consumers' minds and provide a redemptive beat for the company.

"For me it is a big, big deal," says Steven A. Ballmer, Microsoft's chief executive. "There's nothing like it on the market."

Where Apple (NasdaqGS: APPL - News) popularized touch-screen technology, Microsoft intends to bombard the consumer market with its gesture and voice offerings. Kinect technology is intended to start in the living room, then creep over time throughout the home, office and garage into devices made by Microsoft and others. People will be able to wave at their computer and tell it to start a videoconference with Grandma or ask for a specific song on the home stereo.

"I think this is the first thing out of the consumer side of Microsoft in a long, long time where they are in front of everyone else," says Joel Johnson, an editor at large at Gizmodo, the gadget site. "I want a Kinect in every room of my house, watching me and listening to what I am saying. It's so sci-fi and next level that it would be amazing."

The on-time arrival of amazing has become a rare occurrence at Microsoft, a fact not lost on investors or Microsoft's directors.

The company continues to rely on its Windows, Office and business software franchises for the bulk of its $62.5 billion in annual revenue. In high-growth areas like phones and tablets, Microsoft has long sold software but has watched Apple come out of nowhere to gobble up the most profits. With such successes, Apple overtook Microsoft in May as the world's most valuable tech company and has since swelled that lead to more than $62 billion. Microsoft's board gave Mr. Ballmer the fiscal equivalent of a timeout by docking his bonus over the last fiscal year, pointing to lackluster mobile technology and a dearth of innovation. And whether Kinect can revamp Microsoft's image as an innovator remains a big question.

Critics knock Kinect games as too easy and say the gesture technology still has annoying kinks. They also say Microsoft has had a nasty habit of gumming up its creative engines with bureaucracy.

"They often got lost in fights between all their divisions," Mr. Johnson says. "Anytime something becomes high-profile, middle management slows it down."

But with Xbox, Microsoft has so far done right by consumers and has barreled ahead. It has sold 42 million Xbox 360 consoles and has 25 million people signed up for Xbox Live. In September alone, people spent a billion hours using Xbox systems.

Microsoft has long salivated over the notion of controlling the living room and becoming a major entertainment force. Kinect may well stand as its best bet yet for turning that vision into a reality. "This is an incredibly amazing, wonderful first step toward making interactivity in the living room available to everybody," says Mr. Ballmer, while cautioning that Microsoft still has "a lot of work to do."

On a Tuesday this month, Allen Walker, 49, and his son Chris, 16, tested a Kinect car-racing game at the research center. The test room felt clinical with its bare walls, overhead cameras and just a television for company.

Given no instructions on how to use Kinect, the father and son reached the initial game menu on their own in a couple of minutes and saw their virtual selves staring back. They waved, kicked their legs and wiggled a bit, and their avatars followed suit. When the game started, the Walkers tilted left and right to steer, pulled their torsos back to rev up the engine and then thrust forward to accelerate up ramps and soar through the air.

At the end of each game, photos and videos appeared that documented their comical flailing and elicited huge smiles from them. (The photos are likely to become prime Facebook fodder come November.)

Several times, Mr. Walker nudged Chris out of the way to take control of the system, thus embracing the uncommon role of game-play adviser to his son.

Making such complex technology so easy to use bordered on the impossible three years ago, when a small group of Microsoft employees gathered to plot Kinect's future. Plenty of companies have spent decades refining gesture- and voice-recognition technology. Typically, however, it works best in controlled environments. Cameras and sensors that perceive movements often need steady, abundant light, while voice technology tends to hinge on the assumption that a microphone is near a user's mouth.

Microsoft's engineers knew they wouldn't have the luxury of fixed settings with Kinect. They had to build a product that could work just as well in a small Japanese living room as in a spacious Texas-size den. And it would have to adjust for varying light conditions and the raucous commotion of people at different distances from its sensor.

"No one had tried to solve these problems in the consumer space and put all of this together," says Don Mattrick, the president of Microsoft's interactive entertainment business.

For Kinect's eyes, Microsoft turned to PrimeSense, based in Tel Aviv. It links a standard Web camera with a pair of sensors to offer depth perception. One sensor emits light near the infrared range, giving Kinect its own light source impervious to ambient conditions. The other sensor monitors users' distance from the device.

THE eyes were nice, but if only Kinect had a brain.

Adding the smarts required Microsoft's artificial-intelligence experts and thousands of test subjects. Microsoft found people of varying shapes and sizes and recorded how they moved by monitoring 48 joints in their bodies. Over time, the algorithms that digest this data became better and better, allowing the system to work with pregnant women and children in baggy clothes as well as with average-size adults in T-shirts and shorts.

Microsoft upgrades and rewires the Kinect brain every 24 hours and can send updates to Xbox systems via the Internet when it chooses. Kinect recognizes someone it has seen before by body shape, so there's no need to log into the system each time a game is played. It knows your left hand from your right and can distinguish between two players even when their paths cross.

If players have similar builds, Kinect tries to glean differences in their facial features, haircuts, body movements and clothing color. And if identically dressed twins initially stump the system, it will ask each to say something.

"If it can't disambiguate, we say, 'Please tell us if you are A or B,'" says Alex Kipman, incubation director for Xbox 360. "Then, you end up with the equivalent of a different bar code."

On a more futuristic note, Kinect might see that you're wearing a Dallas Cowboys jersey during a football game and switch the commentary to the voices of the Dallas announcers.

For voice commands, the device relies on four microphones in an asymmetrical configuration that helps home in on the person giving commands and separate out the chatter of other people on the sofa. Kinect also knows when sound comes from the TV or from a game and can block the extra noise from interfering with the voice commands.

"If we are serious about shifting the entire computing industry to this world where the devices understand you, then the technology needs to be robust," Mr. Kipman says. "Otherwise, it's just a gimmick."

Surpassing gimmick status may be Kinect's biggest hurdle.

People like Mr. Johnson from Gizmodo note that the first batch of Kinect games differs sharply from the war and adventure sagas that have driven Xbox sales. The weapons have been replaced by water rafts, Ping-Pong paddles and yoga poses through games similar to those that families found with Nintendo's Wii.

"It's not being used to its full potential in gaming yet," Mr. Johnson says of Kinect. "It's mostly Wii-class party games and jumping around."

Sony contemplated advancing its own gesture-recognition technology to the 3-D realm and eliminating controllers, but it decided that gamers wouldn't find the experience satisfactory at this point. Instead, it built Move, a wand-like controller with more sophisticated movement-tracking features than the Wii wand.

"I totally agree that there is this magical feeling with using your hands to select something," says Richard Marks, a senior researcher at Sony Computer Entertainment America, who helped create Move. "But that feeling wears off pretty quickly, and it becomes a pretty cumbersome way to do things."

Sony executives tip their hat to Microsoft for trying something risky, but like some other people who've tested Kinect, say the system seems to lag, hindering truly immersive games. Still, game makers like Harmonix Music Systems describe Kinect as filling a void and credit Microsoft for making something new possible.

Harmonix, which sells the Rock Band music game, will offer Dance Central, a game made for Kinect that teaches dance routines to songs like "Poker Face," from Lady Gaga, and "Bust a Move," from Young MC.

"We've been trying to find technology that would allow the player to use their whole body," says Tracy Rosenthal-Newsom, a vice president at Harmonix. "We wanted to remove the technology and really allow people to dance."

Harmonix hired a team of choreographers to come up with the routines, which range from simple, rhythmic motions to acrobatic affairs that only skilled dancers can handle.

"It really is a toy, and I mean that in the best sense of the word," says Ted Brown, a game designer at Buzz Monkey, which produces games for the major console makers. "There is magic there when you can sort of put on a skin and perform on the stage."

The first Kinect prototype cost Microsoft $30,000 to build, but 1,000 workers would eventually be involved in the project. And now, hundreds of millions of dollars later, the company has a product it can sell for $150 a pop and still turn a profit, Mr. Mattrick says. (People who don't have an Xbox can pay $300 for a package that includes the console, Kinect and a game.)

Microsoft has spent several months marketing Kinect, even setting up a speakeasy-style site in Los Angeles where celebrities like Justin Bieber and Tony Hawk could play games, and drink and eat with friends, after saying a password to gain entry. All told, Microsoft expects to spend "hundreds of millions" to advertise the device, Mr. Mattrick says.

For Mr. Ballmer, Kinect is far more than a business opportunity or a pleasant diversion for consumers. It offers a moment to prove to investors and company directors that Microsoft is capable of an Applesque, game-changing moment under his leadership.

"I'm excited to be way out in front," he says, "and want to push the pedal on that."