Steve Jobs’s disregard for enterprise IT was not a secret. Yet without him, there would be no consumerization of IT. He entirely changed the nature of enterprise computing—accidentally.

Two Apple innovations that pried open the door to the enterprise: the iPod (released in 2001) and iTunes (launched in 2003). The first trained consumers to expect intuitive and accessible mobile technology in their everyday lives, while the second laid the foundation for cloud computing.

The iPod did what laptop computers had not: It put affordable, compelling, portable technology into people’s hands, and it soon became a piece of tech integrated into the masses’ everyday routines. Once the iPod was part of our daily lives, the expectation of ubiquitous and convenient computing power became a permanent assumption.

Then the iPhone came along, and the idea that you’d not be allowed to use a powerful, elegant phone for basic work tasks seemed ridiculous. IT departments may struggle with workers who access unauthorized phones on the job, but users don’t care about IT’s need to control software installations. They just know that the iPhone helps them with their jobs.

As for iTunes, it trained people to be comfortable with navigating remotely administrated software services and virtual assets. The young professionals in today’s workplaces won’t walk into a sys admin’s cubicle and marvel at the library of software boxes there; they’re perfectly fine with software as someone else’s problem someplace else, so long as it works for them.

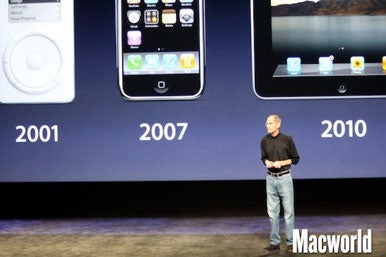

In his Macworld Expo 2001 keynote in San Francisco, Jobs said that the PC was evolving from the productivity era to the digital lifestyle, becoming the hub of people’s everyday activities. In the intervening 10 years, Apple exploded the boundaries of the hub and introduced products that brought technological advances into everyday life.

For most of us, everyday life includes day jobs, so when iPhone-, iPod-, iTunes-savvy people walked into the workplace, they neither knew nor cared that they were moving from one demographic (consumers) into another (enterprise users). These people, who consumed hardware and software products on their own time, wanted the same positive, powerful experiences on the job — thus, paving the way for the consumerization of IT.

Steve Jobs may have never intended to change the enterprise, but he altered the behavior of the people whom the enterprise serves. His accidental legacy in the enterprise is a high-tech version of the spandrels in the cathedral. For those who are savvier at network architecture than classical architecture, spandrels are the curved supports tucked between the arches that support a dome. In many cathedrals, these humble bits of masonry have been co-opted as the canvases for artistic embellishment. To paraphrase Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin’s famous analogy, the spandrels had one use, but were appropriated for another. They were still relevant, but their most compelling application was nowhere near the original function or intention.

In his keynotes, Jobs often touted the ability of Apple’s products to enhance the creative impulses lurking in every computer user; according to the sales pitch, each user is an artist, given the right tools. The iPod, the iTunes Music Store, and the iPhone are Apple’s spandrels. Every consumer is an artist. Collectively, they took products that were never meant to see the inside of a server room and used them to change the very nature of corporate computing.