Ed Hewitt planned to surf all day. The weather reports for the New Jersey coastline called for a blue September sky, warm temperatures, and the right wind for near-perfect surfing conditions.

A 39-year-old watersports enthusiast, Ed woke up early on Sept. 11, 2001.

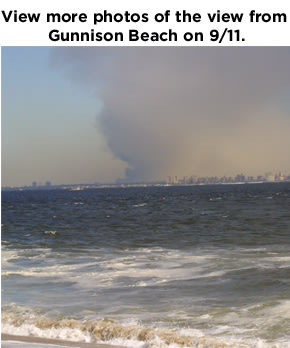

He would surf a spot called Sandy Hook, a lonely spit of sand on the north end of Gunnison Beach that points like a finger toward Brooklyn and Manhattan, which rise out of the water a few miles away. When conditions are just right, you can ride a wave at Sandy Hook for hundreds of yards with the Empire City skyline as your backdrop.

It was one of those days that promised long rides and clear skies, and Ed, a travel writer taking the day off, was stoked. He loaded a 9-foot surfboard into his white minivan and pulled out of his driveway in Kingston, New Jersey, for the hourlong drive.

In the van, he set his cell phone down in the cup holder and cranked up some tunes on the radio. Halfway into his drive along State Road 36, his phone buzzed. Probably best not to check in this traffic, he thought, and ignored the call as he flew toward the beach. The phone buzzed again, signaling a voicemail. Ed ignored it. He was in the zone and feeling good: The radio was blasting, and he could smell the coconut from the fresh wax on his board. In a few minutes, he'd be cruising down the face of a wave.

Ed Hewitt.

He pulled his board out of the van, slipped into a wetsuit and began the trek up the beach toward the point, where he joined a group of people watching the smoke. Suddenly, the black cloud turned white. They didn't know it at the time, but the white smoke was the ash and debris coming from the collapse of the South Tower.

"Everything that was in Manhattan changed color," he recalled later. "It was such a chilling thing to have watched."

Like most people throughout the country at that moment, Ed was unaware of the magnitude of the disaster. Fires are tragic, sure, but they happen all the time. Plane crashes are rare, but life goes on.

Ed felt uneasy, but he decided to hop into the water.

Holding the board under his arm, he stepped up to the shoreline, where the waves were crashing hard. He got a running start from the sand toward the water and plopped belly-first onto the board, paddling furiously. He maneuvered his board over and under the unforgiving waves, the water crisp with the coming of fall, and made it beyond the soup. Exhausted, Ed sat up on his board to catch his breath and realized he was alone. There was an uneasy silence as he looked toward the smoke. But there was little time to focus on that with the next set of waves marching directly toward him.

Ed caught the first wave, dropped in, and pulled off the lip for another one. He kept his eyes on the cloud of smoke, which continued to fill the morning sky.

He sat by himself, straddling his board as the nose bobbed in and out of the lonely water in front of him. The cloud grew larger, more menacing.

A few moments later, he watched as boats loaded with people came speeding in his direction from Manhattan. Hundreds of people were fleeing the island. Many were bloodied and injured.

"I'm sitting in the water and just watching this whole thing, and it really just piled up on me," he said.

In his mind, he saw the faces of his friends who lived in Manhattan. He thought of his wife, and he began to feel sick and anxious. What am I doing here? he thought.

He paddled toward the shore and caught a wave that deposited him on the sand. The crowd on the beach had gathered around a man with a radio. Everyone stood transfixed by the smoke coming from Manhattan.

Ed ran to his car, peeled off his wetsuit, threw the board into the van, and called his wife. Pulling onto the main road, he tried to keep his mind focused. On both sides of his van, drivers as shocked and horrified as he was sped past him.

"I remember trying to make sure that I didn't get killed," he said later. "I didn't feel myself, and I could tell that folks around me didn't feel themselves either. I didn't have my head on my shoulders, and I was very aware of it."

The world had changed in the short time since he'd tossed his surfboard into the van on that peaceful morning. Radio stations were no longer playing feel-good jams. Instead, he listened to news announcers tell the story as fast as they could gather the information, their own voices trembling over the airwaves. The World Trade Center had fallen. The Pentagon, in Washington, D.C., was on fire. A plane had gone down in Pennsylvania. Thousands could be dead. America had been attacked.

All this while Ed Hewitt sat alone in the ocean, watching it unfold.

Back in Kingston, he pulled the van into the driveway and ran into the house, where his wife was waiting for him.

"I got home and was very quickly put to work," he said.

His wife was a coach for a Princeton University rowing team, and she and Ed stayed connected to many of the rowers in the area through Row2k.com, which Ed had created for rowing enthusiasts. That morning, they started compiling a list of survivors in the local rowing community. Ed got on the phone, then blasted a mass email to rowers in the area and took down the names that could be accounted for.

Emails and phone calls poured in with stories of narrow escape from the buildings that went down. His closest friends, who worked in the World Trade Center, had made it out alive.

As the days passed, more rowers added their names to the list. But not everyone responded. Families continued to search, and emergency workers stayed up all night, searching for people trapped in the rubble.

"It was a very intense couple of weeks waiting for people to be alive," Ed said. But he kept at it and became the point of contact for rowers in the Northeast who were affected by the attacks.

In the end, Ed helped arrange the funerals of five rowers who never surfaced.

Looking back, it's not the surfing that Ed thinks about first. He thinks of the people he helped and the late nights he spent waiting to hear whether they made it out.

"We were working so hard to find people," he said. "That's the part that really sticks with me."

When the conditions are right, Sandy Hook still breaks, with gorgeous rollers that serve up epic rides along the point. But you won't find Ed Hewitt gliding across the water. He still likes to surf, but not there. Anywhere but there.

"The photos of it, I can't bear to look at them," he said. "There's no way I would go out to GunnisonBeach to go surfing."

Ed is nearly 50 now, and he's spending the 10th anniversary of the tragedy with his wife and their 4-year-old son, Connor. He's also organizing a memorial on Row2k.com.

And someday, when Connor is old enough, Ed may take his son to the place where he sat alone in the ocean and watched the world change.