Imagine a computer so small it could slip through the human bloodstream. At just a millimeter in width, a new battery built by a Harvard University and University of Illinois team is perfectly suited to be a power source for tiny computers. It is also the first battery to ever be fabricated with a 3D printer.

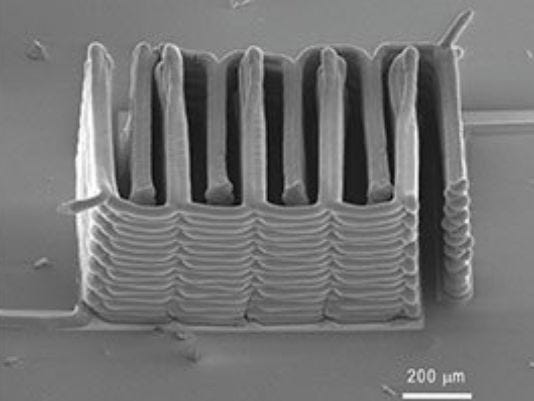

The team used a custom printer and ink to produce the batteries. A nozzle .03 millimeters–or 30 microns–wide deposited layers of nanoparticle-packed paste in a comb-like shape. A second printed comb nestled into the first, their teeth interlocked. These functioned as the two halves of electrodes, which conduct electricity.

After printing, the electrode layers quickly hardened and were placed in a small container filled with solution. The finished product measured in at less than a millimeter wide. The team published their work Tuesday in Advanced Materials (subscription required).

A battery like this could transform fields like robotics, which are limited by how small they can build product by currently available materials. It would benefit tiny flying and swimming drones that must work autonomously over long distances, plus medical implants and discrete, wearable electronics.

Co-author Jennifer Lewis mentioned Harvard's Robobees–tiny autonomous drones–as a potential application.

"The idea to be able to integrate small sources directly onto those kinds of robotic insects would be powerful and enabling. Right now, everything is tethered to an electric power source. It would be very nice not to have that," Lewis said.

Other small batteries are made of layers of film, but are too thin to provide much power. This 3D printed variety is dense and thick enough to compete with a traditional battery, and it's also a lithium-ion battery: the same style as in a cell phone.

"The electrochemical performance is comparable to commercial batteries in terms of charge and discharge rate, cycle life and energy densities. We're just able to achieve this on a much smaller scale," co-author Shen Dillon said in a Harvard release.

Next, the team wants to make larger batteries that can be directly printed inside another object. Right now, hearing aids are 98 percent 3D-printed and electronic components must be added later.

"Why not print the whole hearing aid?" Lewis said. LINK