NEW YORK (AP) — By the time 10-year-old Sarah Murnaghan finally got a lung transplant last week, she'd been waiting for months, and her parents had sued to give her a better shot at surgery.

Her cystic fibrosis was threatening her life, and her case spurred a debate on how to allocate donor organs. Lungs and other organs for transplant are scarce.

But what if there were another way? What if you could grow a custom-made organ in a lab?

It sounds incredible. But just a three-hour drive from the Philadelphia hospital where Sarah got her transplant, another little girl is benefiting from just that sort of technology. Two years ago, Angela Irizarry of Lewisburg, Pa., needed a crucial blood vessel. Researchers built her one in a laboratory, using cells from her own bone marrow. Today the 5-year-old sings, dances and dreams of becoming a firefighter — and a doctor.

Growing lungs and other organs for transplant is still in the future, but scientists are working toward that goal. In North Carolina, a 3-D printer builds prototype kidneys. In several labs, scientists study how to build on the internal scaffolding of hearts, lungs, livers and kidneys of people and pigs to make custom-made implants.

Here's the dream scenario: A patient donates cells, either from a biopsy or maybe just a blood draw. A lab uses them, or cells made from them, to seed onto a scaffold that's shaped like the organ he needs. Then, says Dr. Harald Ott of Massachusetts General Hospital, "we can regenerate an organ that will not be rejected (and can be) grown on demand and transplanted surgically, similar to a donor organ."

That won't happen anytime soon for solid organs like lungs or livers. But as Angela Irizarry's case shows, simpler body parts are already being used as researchers explore the possibilities of the field.

Just a few weeks ago, a girl in Peoria, Ill., got an experimental windpipe that used a synthetic scaffold covered in stem cells from her own bone marrow. More than a dozen patients have had similar operations.

Dozens of people are thriving with experimental bladders made from their own cells, as are more than a dozen who have urethras made from their own bladder tissue. A Swedish girl who got a vein made with her marrow cells to bypass a liver vein blockage in 2011 is still doing well, her surgeon says.

In some cases the idea has even become standard practice. Surgeons can use a patient's own cells, processed in a lab, to repair cartilage in the knee. Burn victims are treated with lab-grown skin.

In 2011, it was Angela Irizarry's turn to wade into the field of tissue engineering.

Angela was born in 2007 with a heart that had only one functional pumping chamber, a potentially lethal condition that leaves the body short of oxygen. Standard treatment involves a series of operations, the last of which implants a blood vessel near the heart to connect a vein to an artery, which effectively rearranges the organ's plumbing.

Yale University surgeons told Angela's parents they could try to create that conduit with bone marrow cells. It had already worked for a series of patients in Japan, but Angela would be the first participant in an American study.

"There was a risk," recalled Angela's mother, Claudia Irizarry. But she and her husband liked the idea that the implant would grow along with Angela, so that it wouldn't have to be replaced later.

So, over 12 hours one day, doctors took bone marrow from Angela and extracted certain cells, seeded them onto a 5-inch-long biodegradable tube, incubated them for two hours, and then implanted the graft into Angela to grow into a blood vessel.

It's been almost two years and Angela is doing well, her mother says. Before the surgery she couldn't run or play without getting tired and turning blue from lack of oxygen, she said. Now, "she is able to have a normal play day."

This seed-and-scaffold approach to creating a body part is not as simple as seeding a lawn. In fact, the researchers in charge of Angela's study had been putting the lab-made blood vessels into people for nearly a decade in Japan before they realized that they were completely wrong in their understanding of what was happening inside the body.

"We'd always assumed we were making blood vessels from the cells we were seeding onto the graft," said Dr. Christopher Breuer, now at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. But then studies in mice showed that in fact, the building blocks were cells that migrated in from other blood vessels. The seeded cells actually died off quickly. "We in essence found out we had done the right thing for the wrong reasons," Breuer said.

Other kinds of implants have also shown that the seeded cells can act as beacons that summon cells from the recipient's body, said William Wagner, director of the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. Sometimes that works out fine, but other times it can lead to scarring or inflammation instead, he said. Controlling what happens when an engineered implant interacts with the body is a key challenge, he said.

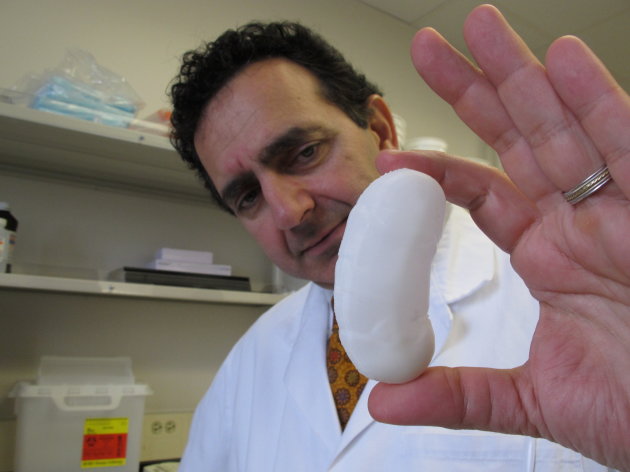

So far, the lab-grown parts implanted in people have involved fairly simple structures — basically sheets, tubes and hollow containers, notes Anthony Atala of Wake Forest University whose lab also has made scaffolds for noses and ears. Solid internal organs like livers, hearts and kidneys are far more complex to make.

His pioneering lab at Wake Forest is using a 3-D printer to make miniature prototype kidneys, some as small as a half dollar, and other structures for research. Instead of depositing ink, the printer puts down a gel-like biodegradable scaffold plus a mixture of cells to build a kidney layer by layer. Atala expects it will take many years before printed organs find their way into patients.

Another organ-building strategy used by Atala and maybe half a dozen other labs starts with an organ, washes its cells off the inert scaffolding that holds cells together, and then plants that scaffolding with new cells.

"It's almost like taking an apartment building, moving everybody out ... and then really trying to repopulate that apartment building with different cells," says Dr. John LaMattina of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He's using the approach to build livers. It's the repopulating part that's the most challenging, he adds.

One goal of that process is humanizing pig organs for transplant, by replacing their cells with human ones.

"I believe the future is ... a pig matrix covered with your own cells," says Doris Taylor of the Texas Heart Institute in Houston. She reported creating a rudimentary beating rat heart in 2008 with the cell-replacement technique and is now applying it to a variety of organs.

Ott's lab and the Yale lab of Laura Niklason have used the cell-replacement process to make rat lungs that worked temporarily in those rodents. Now they're thinking bigger, working with pig and human lung scaffolds in the lab. A human lung scaffold, Niklason notes, feels like a handful of Jell-O.

Cell replacement has also worked for kidneys. Ott recently reported that lab-made kidneys in rats didn't perform as well as regular kidneys. But, he said, just a "good enough organ" could get somebody off dialysis. He has just started testing the approach with transplants in pigs.

Ott is also working to grow human cells on human and pig heart scaffolds for study in the laboratory.

There are plenty of challenges with this organ-building approach. One is getting the right cells to build the organ. Cells from the patient's own organ might not be available or usable. So Niklason and others are exploring genetic reprogramming so that, say, blood or skin cells could be turned into appropriate cells for organ-growing.

Others look to stem cells from bone marrow or body fat that could be nudged into becoming the right kinds of cells for particular organs. In the near term, organs might instead be built with donor cells stored in a lab, and the organ recipient would still need anti-rejection drugs.

How long until doctors start testing solid organs in people? Ott hopes to see human studies on some lab-grown organ in five to 10 years. Wagner calls that very optimistic and thinks 15 to 20 years is more realistic. Niklason also forecasts two decades for the first human study of a lung that will work long-term.

But LaMattina figures five to 10 years might be about right for human studies of his specialty, the liver.

"I'm an optimist," he adds. "You have to be an optimist in this job."